I’m an electrical engineer and I understand technology. And there you have two lies, back-to-back, to start this month’s diatribe/discussion.

I’m an electrical engineer and I understand technology. And there you have two lies, back-to-back, to start this month’s diatribe/discussion.

As to being an engineer, the truth is that once, long ago, I had enough proficiency in mathematics to receive enough passing grades in engineering courses to convince the University of Florida to confer upon me a bachelor’s degree and give me a map out of town. As to understanding technology, I understand that if I try to adjust the touch screen controls in my Ram pickup while driving, sooner or later, and probably sooner, I’m going to run into something. Ok, I do understand a little more about how things work than that, but not much more, in the greater scheme of things. Fortunately for me, when it comes to understanding technology, I have my brother-in-law Don, who understands most things mechanical, and my old friend Tanner, who understands a lot about how most anything and everything works, and we talk often. And while either may be mistaken once in a blue moon, he is not like our friend Google, who just makes stuff up to fill the page.

Rule One, based upon my beliefs: Don’t believe everything you read! Rule Two: Have some friends who know stuff you don’t!

I have a brother who’s big on differentiating what he knows from what he believes. I believe this is a great idea for all of us to undertake on a regular basis. Perhaps if everyone did this, we’d have a little less hubris and a little more courtesy in our public discourse, but, hey, call me a dreamer.

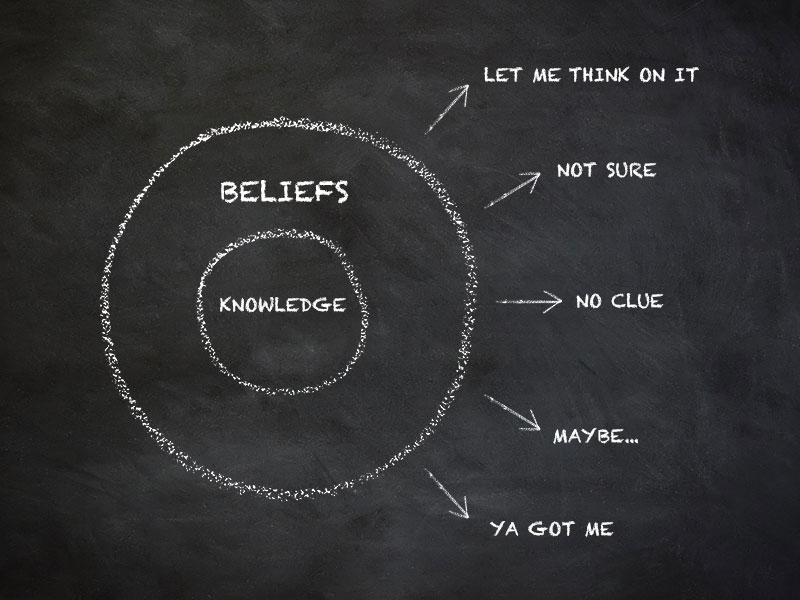

A diagram of my very own knowledge base might be useful here:

We can spend a lot of time discussing whether something is known or merely a belief, but we are not taking a freshman philosophy class here.

Our aim is to be clearer in our thinking to get us through life in a mostly productive fashion, so yes, we can agree that we do know that 2 + 2 is 4, while we only believe that sound does not travel through a vacuum, and therefore, “In space, no one can hear you scream.”

Once again, being part of the human race, we can argue ‘til the cows come home that we do, in fact, know that sound cannot travel through a vacuum because (a) the mechanics of sound travel indicate that matter is needed to transmit sound, and (b) it has been proven via experiment. As for me, however, I haven’t seen the experiment, so while I completely believe it, I concede that I don’t actually know it.

And how, pray tell, is this discussion useful in any aspect of life, or since I have to say investing at least once, or they will take away my monthly column access, or investing. There. I got it in. Twice. Phew. Now we can all relax and return to our diagram.

When you are operating in your knowledge base, go ahead and be dogmatic.

Defend the truth. Truth matters and is not subjective, as our culture likes to insist. Stand firm in what you know.

When we are outside our knowledge base and have moved into beliefs, it is time to dial down the dogma. Be firm in your presentation of your case, be committed to your beliefs, and hold to your values … but be aware of the possibility you might be wrong. This will require a commitment to listening to others. This may be painful and difficult, and it may register a zero on the fun meter.

But the biggest part of the diagram, by volume, is “Things I Don’t Know”. Please notice, if you haven’t already, while the areas circumscribed by “Knowledge” and “Beliefs” are finite, the Things I Don’t Know is/are infinite.

And here we are, once again, talking about investing. (That’s three mentions, if you’re counting.)

Berkshire Hathaway recently held their annual meeting, wherein Warren Buffett announced the upcoming end of his tenure as CEO of the company.

During the meeting, he (Mr. Buffett) restated the wisdom that (perhaps) originated with Charlie Munger. Charlie, when called upon to describe why they were more successful investors than most, replied, “We’re not smarter, we’re just less stupid.”

During the meeting, he (Mr. Buffett) restated the wisdom that (perhaps) originated with Charlie Munger. Charlie, when called upon to describe why they were more successful investors than most, replied, “We’re not smarter, we’re just less stupid.”

And there, dear friends, is a philosophy to guide one’s life. Barry Ritholtz, in his recently published book, How Not To Invest, hammers this point home by emphatically telling us that one of the keys to successful investing (4) is to “avoid unforced errors”. He uses a great example of comparing professional tennis players to amateurs. Professional tennis players, he explains, win by attacking their opponents and placing shots where the opponent cannot return them. Amateurs, however, win by avoiding mistakes; by a dogged persistence focused on getting the ball back over the net and in play. I love that.

With apologies to Mr. Ritholtz for stealing his verbiage, here is Rule Three: “Avoid unforced errors.” Restated in my native Polk County colloquialism, this would read: “Don’t be stupid.”

Shall we become contrarians like so many on social media aspire to?

Shall we make stupid investing or life decisions? (Some of these are rhetorical.) Confuse what we believe with what we know and then be dogmatic about it; that will get us to where we don’t want to go. Start believing the stock market will go up/down because x/y happened, and we can now be day traders! Nope, we don’t have to be that smart, we just have to avoid being that stupid!

Warren Buffett, when cautioning against leveraging (borrowing money) against your stock holdings, counseled, “The market can behave irrationally longer than you can stay solvent.” There are endless examples of how we can outsmart ourselves, on our way to investing (five!) success, and there will always be hucksters selling us the snake oil. Like Chief Dan George almost said one time, “You made it, you drink it.”

Sometimes, it is as simple as Nancy Reagan said. “Just say no.”

PS: Today’s word is hubris. This is probably a layup for you, but we should probably introduce it into our daily vocabulary more often. Heaven knows we see enough examples out there.

June 2025